Segment one of a four part blog series by Ten Across digital journalism fellow Taylor Griffith. In this series Taylor reflects on current goals, collaborations and strategies for building resilient communities across the naturally inundated southern U.S. region.

Last time, I spoke to my experience of reporting in Coolidge; a small, historic farming town in Pinal County. It was here, I observed a general disconnect between our knowledge of the dwindling Colorado River and finite state groundwater supplies, and the continued residential and industrial development upon those lands increasingly vulnerable to drought and aridification.

As it turns out, we have known for much longer than communities like Coolidge have existed that one day our demand for water in the west would far exceed our supply. The result of this imbalance is being brought to bear today, as the Arizona Department of Water Resources reports that from 2016 to 2115, Pinal County is expected to experience over eight million acre-feet of unmet demand in groundwater supply.

Earlier this year, ADWR issued a similar warning to developments in west Phoenix.

An arid west

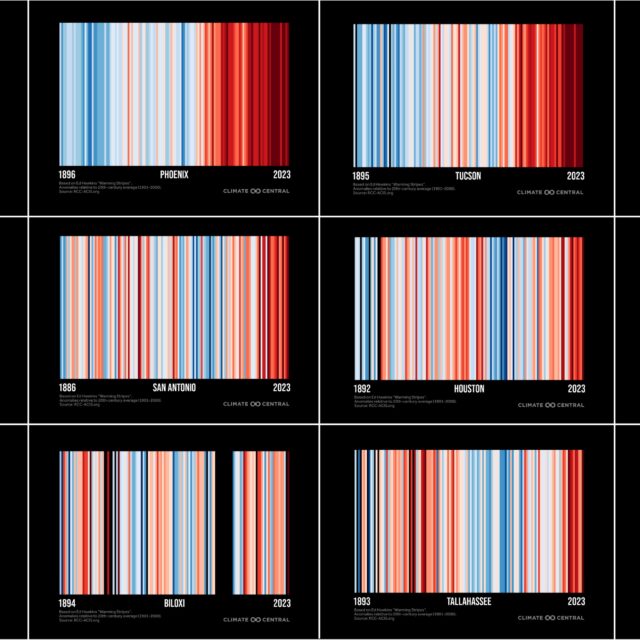

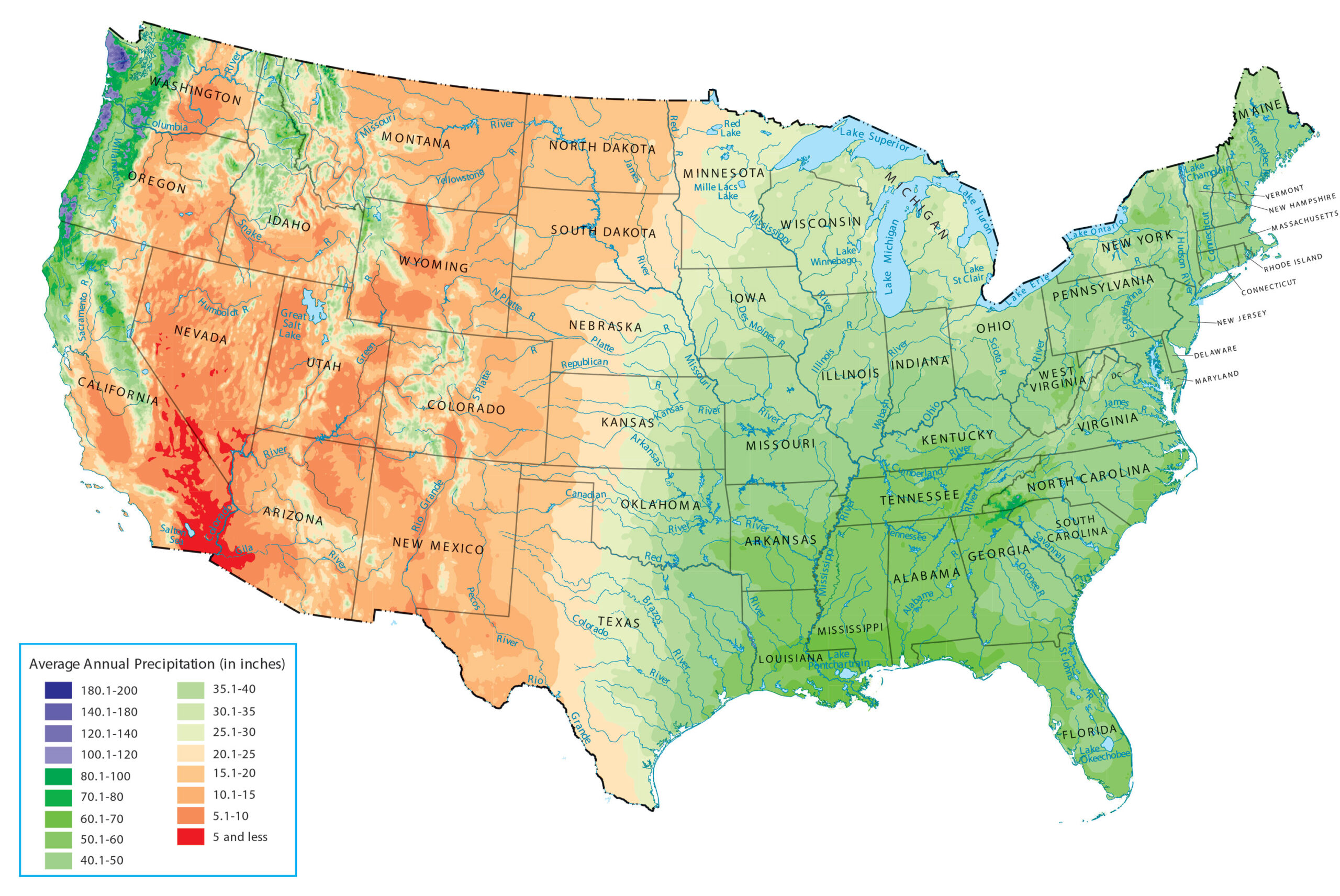

Even prior to a warming climate becoming first, widely accepted, and second, an expected catalyst for dramatic environmental and demographic change in our nation, we have historically questioned the viability of settlement in the arid west.

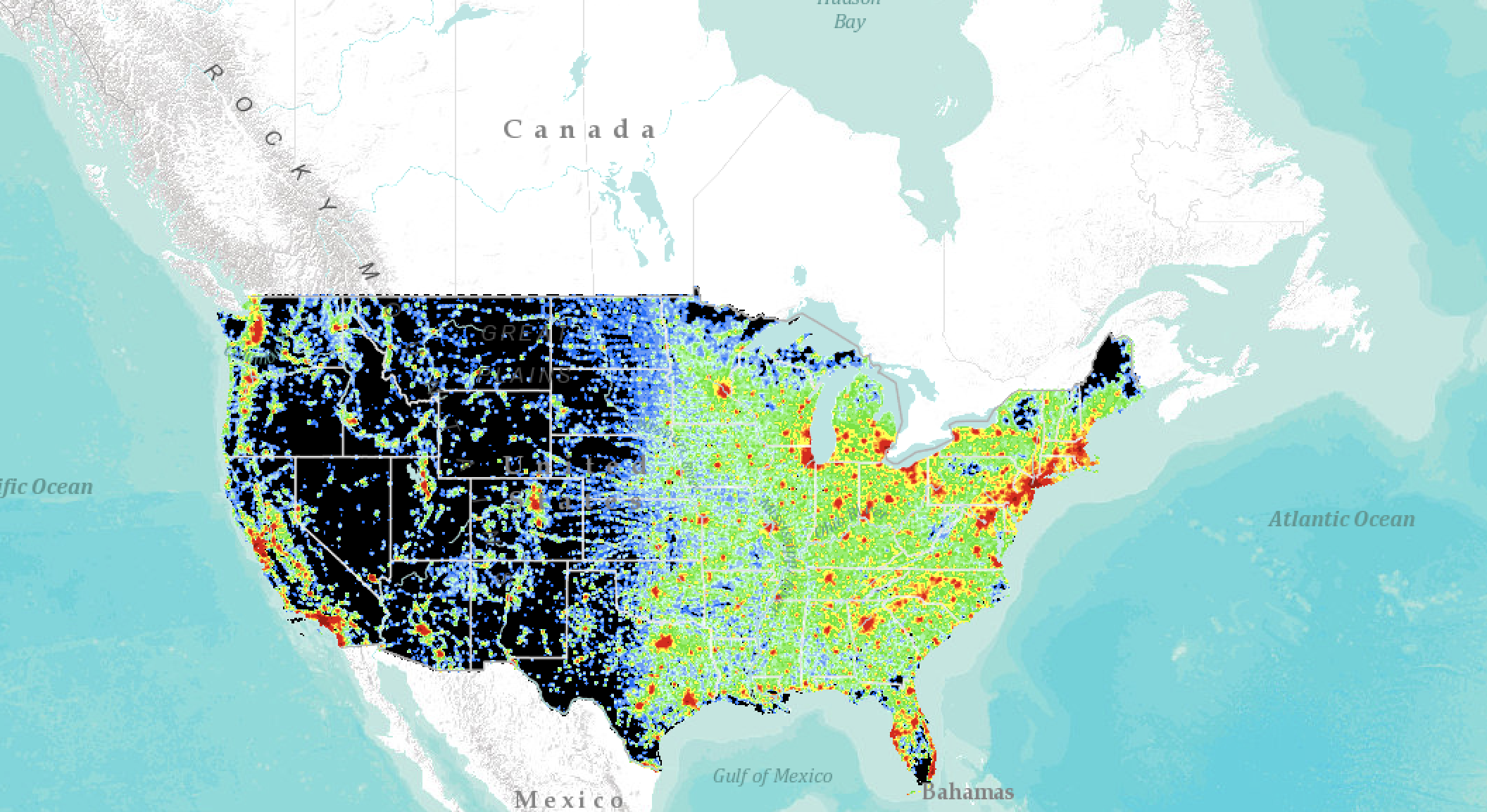

The bright greens and reds in the map above represent the most densely populated areas of our nation today. The harsh drop-off in population density is observed almost exactly along the similarly located and unwavering 20-inch annual precipitation line.

The modes of Westward Expansion were not just unethical in their decimation, confinement, and theft of natural resources from Indigenous communities, they were also largely void of any hydrologic consideration for our western water supply. Not that one man didn’t at least try to prevent the latter.

At a U.S. Senate committee hearing in 1890, lifelong explorer and scientist John Wesley Powell, delivered a well-informed warning for the future of water in the region. Not only did previous visions of a verdant west appear far from possible, but Powell even brought into question aspirations for sustaining large scale development and agriculture upon these lands with his presentation of the first hydrologic map of the west.

Twenty-three years into a historic megadrought; with a drying Colorado River and potential loss of hydropower at Glenn Canyon Dam, Powell’s predictions contain an eerie gravity as leaders at all levels of government attempt to address a supply and demand imbalance of well over 2-million-acre feet a year throughout the basin.

Though it seems a fresh crisis for the region, this is not the first time central Arizona has been forced to rethink its water portfolio to sustain current habitation.

Managing supply

The Central Arizona Project was conceptualized as early as the 1930s and completed in 1993. Still considered an engineering marvel, pulling Colorado River water 336 miles across the Arizona desert in a concrete-lined canal system, it was a necessary, aqueous lifeline as demand on the Gila River and local aquifers began to buckle under the weight of a booming cotton industry in Pinal County and growing Phoenix metropolis.

Currently serving 80% of the state’s population, this canal system is increasingly on the verge of becoming a relic of the past should the seven river basin states fail to come to a consensus on individual annual allocations in time to stave off a crash of the Colorado River.

The magnitude of this water crisis has prompted a regional rethinking of resource management, which you can learn more about in our latest podcast episode.

But what I would like to center in this column — and what combines two existential questions for communities along the southern U.S. limits — is the increasingly popular concept of diverting water from a frequently inundated region to this arid one, in hopes of solving one disaster with another.

Opposite ends of the water spectrum

Though not reflected in current population growth numbers or housing market rates; Arizona, Texas, Florida and Louisiana and other states near the equator, are forecast as ground zero regions for a mass residential exodus over the coming century, as a warming climate continues to sap rivers, fuel devastating hurricanes and bury entire communities under its floodwaters. For reference see Jake Bittle’s, The Great Displacement; an essential reading on this topic.

But what if we were to find a way to divert and treat floodwaters or seasonal overflows from the Mississippi River for use in the drought-starved west?

Featuring perspectives from Arizona and Louisiana water experts and a revered civil engineer and innovation officer, The ‘Big Pipe’ Solution panel discussion at the 2023 Ten Across Houston summit dove into what many would consider the next flagstone U.S. infrastructure project to succeed CAP for water acquisition in the west: a major water pipeline from the Mississippi to the parched Colorado River.

The CAP was a widely contested project from concept to completion, a timeline which spans 50 years, as panelist and water resources management advisor for the City of Phoenix Cynthia Campbell explained, “…and I don’t know that we have the luxury of that time in the discussions we’re having right now.”

This sense of urgency was understood by Justin Ehrenwerth, President and CEO of The Water Institute.

Every 100 minutes, Louisiana loses a football field of land mass to rising tides. Since the 1920s, the state has lost an amount of landmass equivalent to the state of Delaware.

All the while communities in the southwest are having to contend with the rapid evaporation of all surrounding moisture, Gulf Coast communities are trying to survive amid a near-annual barrage of biblical tides and storms.

Therefore, Ehrenwerth says for the situation in the west; “we have to consider this (pipeline), we have no choice.” This necessity comes especially at a time in which settlement in the west is questioned nearly as often as life within the Gulf as Ehrenwerth explained:

“We experienced this again after Katrina in New Orleans, there were many people who said, ‘why are you going to rebuild?’ We hear that a lot after many hurricanes, not just in Louisiana, but across the Gulf. And there are conversations… around ‘are there communities that cannot maintain their way of life going forward?'”

Nonetheless, there are obvious legal and financial barriers to such a project, as well as incredible consideration to have for the communities which a major water pipeline might disrupt or remove resources from. As moderator and professor of water law at Arizona State University Rhett Larson explained; water is not a resource many communities will readily volunteer.

“Water is a symbol of sovereignty that has political value,” he said. Which is why, an inter-basin transfer of water would be rife with potential riparian rights lawsuits that would immediately default to the Mississippi users.

On the development side of things, “it’s going to take time,” said John Take, EVP and Chief Growth and Innovation Officer of Stantec, “because when we do move fast as engineers and scientists, we can inadvertently break things.

“We saw that in Flint — the City of Tucson substantially dodged a serious issue by combining water sources in the past. We need to think about the communities on either end of that pipeline, the people whose backyards this might roll through along the way.”

Hailing from Louisiana, a state that is no stranger to seemingly insurmountable water challenges as they are attempting to restore 21 square miles of wetlands by 2070 with the Mid-Barataria Sediment Diversion project, Ehrenwerth offered a series of pathways toward a solution for the west.

“None of this is to say that it (the pipeline) shouldn’t be done,” said Ehrenwerth, although, heavily recommending a more holistic and concerted evaluation of all possible alternatives — among them being the potential for a national water policy that would ensure any solution approach, “…can be informed by the best possible science across a large time scale.”

There is direct evidence that massive climate-related infrastructure can be implemented when that nation is uniformly sobered to the issue at hand, he explained. “…. Post-Katrina in New Orleans, you saw a 14.5-billion-dollar levee reconstruction done faster than anyone had ever even imagined… we know we can build, we know we can move through even regulatory hurdles if the nation is focused,” said Ehrenwerth.

Accelerated, equitable and fact-based approaches across traditional boundaries are going to need to become the norm in our changing world. As we’ll discuss in the next column, without this style of approach, we will perpetuate an exhaustive history of social injustices, now at an unprecedented, highly visible scale.

About Taylor

Taylor Griffith was born and raised in Chandler, a city just outside of Phoenix, Arizona. As a proud citizen of this beautiful, diverse, and sometimes relentlessly hot state; issues related to water, equity, and climate change are influential to her work as the current digital journalism fellow at Ten Across and previous bylines in The Coolidge Examiner.