Authors: Wellington “Duke” Reiter, Ten Across Founder and Executive Director and Taylor Griffith, Ten Across Podcast and Digital Media Producer Fellow

Water, either too much or too little, is a fundamental aspect of the Ten Across project.

On Tuesday, Ten Across founder Duke Reiter was invited to moderate a discussion about water augmentation for the arid state of Arizona. More specifically, the option of a 2,000-mile desalinated water pipeline from the Sea of Cortez into Central Arizona.

Organized and hosted by the Arizona State University Global Center for Water Technology, this panel included: Glenn Williamson, Chairman of the EPCOR USA Advisory Board; Chelsea McGuire, Assistant Director for External Affairs at the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority of Arizona (WIFA); Kerri Hickenbottom, Assistant Professor of Chemical and Environmental Engineering at the University of Arizona; and John Take, Chief Growth and Innovation Officer for Stantec.

While the mechanical movement of water hundreds of miles across varied terrains might appear a radical notion, it is in fact central to the history of Arizona. The metro regions of Phoenix and Tucson and the state’s robust agricultural industry upon which the nation depends, are functions of the Colorado River’s bountiful flows over the previous century. Access to that water is made possible by an audacious canal system, the Central Arizona Project (CAP), which moves water over 300 miles, and in some cases uphill.

But, a recent 23-year-and-counting megadrought on an already overallocated Colorado River has led to significant cutbacks for the state and other junior water rights holders. Approximately 36% of Arizona’s water supply currently comes from the drought-stricken river and following preventive conservation measures, the state has lost 21% of its historic allotment. The implications of this supply reduction are daunting and require Arizonans to once again come together around an ambitious solution for obtaining a long-term water supply. Conversations like the one held on Tuesday are crucial for moving us toward this goal.

Below are a few of the salient themes from the discussion.

Questioning the pace of growth

The scale of the desalination project in question necessarily raises issues of supply and demand, including whether or not the latter is being responsibly and thoughtfully managed.

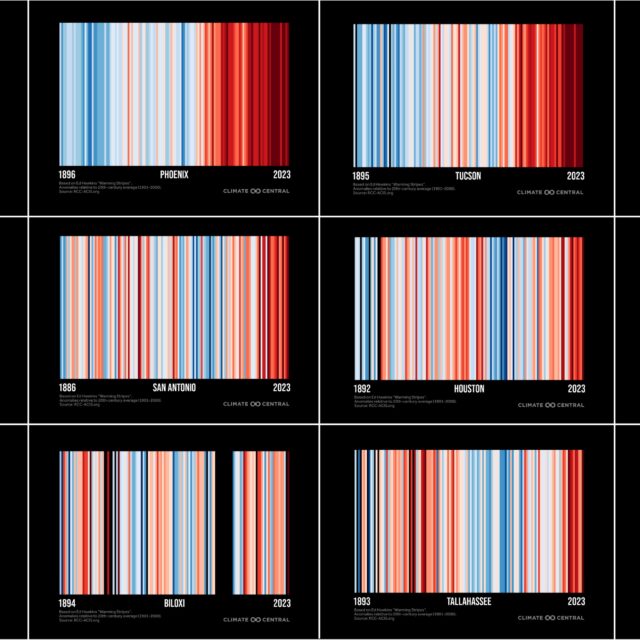

In the post World War II era, the growth of the Phoenix region has been profound in terms of population and low profile land consumption. This format of building combined with a diminished water supply and rising temperatures, is putting the city’s future in a different light.

This summer, a report from the governor’s office projected that four percent of the Phoenix metro area’s 100-year groundwater supply would not be met and that certain developments would need to be stalled. This questioning of the viability of economic or residential growth within and on the outskirts of the city was a wake up call quickly picked up and circulated by the national press.

While some media portrayals of the situation became sensationalized, there is indeed a strong motivation to ensure a robust potable water supply for the future of Arizona and to evaluate options with a sense of urgency, something which Mr. Williamson articulated. Accordingly, state lawmakers recently dedicated $1 billion for procuring and completing innovative water augmentation projects. Ms. McGuire deftly walked through WIFA’s recently issued Request for Information (RFI) seeking viable augmentation project proposals, including large-scale desalination, that would be financed using these state funds.

Solutions require the reconsideration of boundaries

Desalination—the process of removing salt from seawater to render it safe for residential or industrial use—is a mature technology and used throughout the world. Most of these plants are situated in close proximity to the coasts and cities they’re servicing. However, the Sea of Cortez plant would be attached to only the second international water pipeline and would need to transport treated water 1,200 miles uphill, thus requiring considerable energy and technical expertise to execute.

Arizona is no stranger to negotiating across jurisdictional boundaries and maintaining ambitious infrastructure in order to import water from remote locations. A singular example being the aforementioned Central Arizona Project (CAP), which required many decades of lobbying state interests on the Colorado River, and an act of Congress to achieve. However, this was a 336-mile freshwater transport project.

A theoretical pipeline from Puerto Peñasco presents a slew of sensitive environmental and political considerations between Arizona and Mexican officials as it travels from one of Mexico’s most successful tourist and fishing destinations, through two federally protected desert sites within Arizona.

Sonora, Mexico, the state in which the proposed plant would reside, is in the midst of severe drought and in need of water solutions of its own. While desalination could support both states, it requires the disposal of brine byproduct either back into the ocean or elsewhere. This, along with the intake of seawater, presents potentially harmful implications for local marine life within the Sea of Cortez, which is currently home to 50% of Mexico’s fishing capital.

Therefore, all of the panelists agreed that a proposal such as this one must address local needs and conditions from the outset as part of a comprehensive concept.

Cost as the Driver of Change

Desalinated water does not come cheap. The projected cost for Puerto Peñasco’s treated water is $2,000 to $3,000 per acre-foot (equal to about 325,000 gallons). This is comparable to the current rate for treated water from the Carlsbad Desal Plant in California.

Arizona water famously comes at an extremely low cost in comparison to its scarcity, ironically making it a contributor to the state’s potentially unsustainable growth. Mr. Take estimated wholesale water in Arizona currently comes at a cost of roughly $300 or less per acre-foot.Take suggested that a more commodified price will inspire more thoughtful use of this precious resource, something he has already observed regarding water use behaviors in Tucson.

But the implications of a tenfold increase in the cost of water, if that were to become the norm or closer to it, is hard to comprehend in real terms. It would have dramatic implications for the state and will require a complete rethinking of how we inhabit this desert region, our economy, and the lives of the citizenry.

Final Thoughts

A bi-national project of this magnitude will require a transparent address to matters of international relations, politics, equity, and local environments at a scale and depth we have yet to realize up to this point.

But, as audience member, Professor Enrique Vivoni, astutely observed within the final moments of the discussion—Arizona and Sonora leaders are weighing the economic, environmental, and cultural benefits of a conceptual transborder “mega region,” which might include a remedy to our shared water challenges.

That these discussions between bordering nations have begun to take place is a confirmation of the central intent behind the Ten Across initiative. Nearly all the major challenges of the 21st Century are boundaryless, and will require us to think and work across political and jurisdictional lines in order to achieve desirable and equitable outcomes.

Listen to the full discussion.