Listen and subscribe to us on your favorite podcast platform:

…Louisiana can be a model. The Gulf Coast can be a model for the rest of the country and the rest of the world… So, we’ve got to think about every time we do something, how are we leaving breadcrumbs that the next person can pick it up? Whether it’s a… publication in a scientific journal, if we’re using technology to develop something, how are we putting that code out there for other people to run with? How are we creating products and tools that people can go and run with and not just have useful solutions, but actually use them?

—Beaux Jones, president and CEO of The Water Institute

Louisiana’s coast sits at the mouth of the Mississippi River. The largest discharge basin in the United States, the Mississippi collects runoff from 41% of the nation’s rivers and delivers it into the Gulf of Mexico. Where this freshwater meets the ocean, randomly deposited mounds of river sediment form a large, well-inhabited delta that is constantly reordering itself.

To assert permanence upon this fluid landform and to stop severe flooding of riverine communities, the US Army Corps of Engineers introduced the Mississippi River Tributaries Program in 1927. Over the course of four decades, a labyrinth of concrete levees, floodways, reservoirs and pumping stations were constructed in an attempt to control the river.

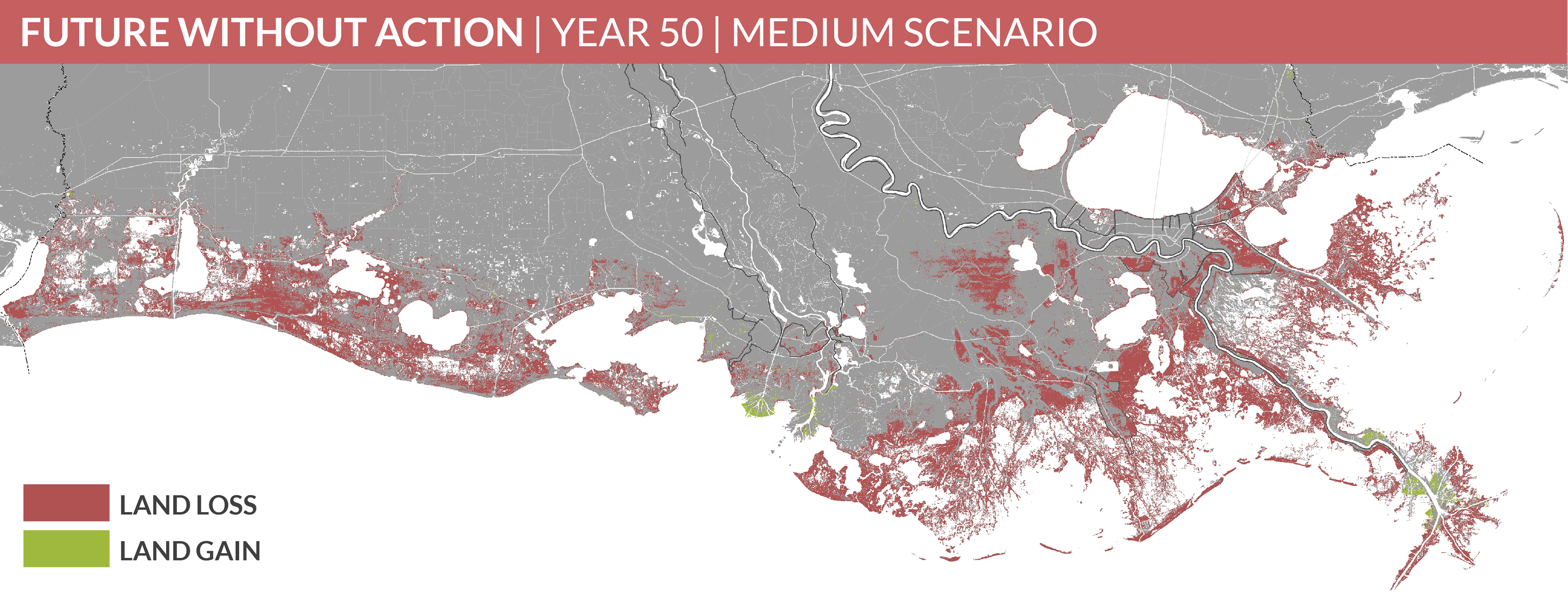

Today, these interventions along the Mississippi are inadvertently leading to greater flooding by preventing the natural process of sediment flow and the formation of new wetlands. Faced with this challenge, as well as the fastest rate of climate-induced sea level rise in the world—the Louisiana delta is quickly receding. In fact as Beaux Jones, president and CEO of The Water Institute shared, the state “loses roughly the equivalent of a football field every 100 minutes.”

This land loss is so great, that the nation’s first official climate refugees hail from a now-deserted island in southern Louisiana: Isle de Jean Charles. Louisiana resident and writer Nathaniel Rich recently commented in The New York Times that evidence suggests New Orleans may not be far behind.

The urgent challenge of protecting the habitation of Louisiana’s coast reminds us that climate change impacts are not a far-off abstraction or that resilience is a distant need; it is a daily reality for those in Gulf Coast.

Listen in as Ten Across founder Duke Reiter and Beaux Jones, president and CEO of The Water Institute, explore how this Baton Rouge-based research center is gathering the best coastal hydrologic data and experts, and sharing their methodologies with the US Army Corps of Engineers and many impacted communities in the I-10 corridor to assist them in critical decision making and resilience planning.

Relevant links and resources:

Learn more about how The Water Institute is helping the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers update their benefit-cost analysis for climate adaptive infrastructure.

Resilient Jacksonville: the award-winning resilience plan from the City of Jacksonville, with research support provided by the Institute

Learn more about The Water Institute’s work at the forefront of quantifying the impacts of compound flooding.

Guest Speaker

Beaux Jones is the president and CEO of The Water Institute. Prior to joining the Institute, Beaux was environmental section chief of the Louisiana Department of Justice, where he represented the state on a variety of matters ranging from environmental and coastal law to criminal and appellate law. He most recently worked as an environmental and coastal lawyer for the firm Baldwin Haspel Burke & Mayer. Beaux was also on the BP spill litigation team with the Louisiana Attorney General.