The recent “Dangerous by Design” study conducted by Smart Growth America showed pedestrian deaths on U.S. roadways hit a 40-year high in 2022. That year’s 7,522 fatalities were a continuation of an upward trend over the preceding decade that was undeterred by government lockdowns or the rise in remote work that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic.

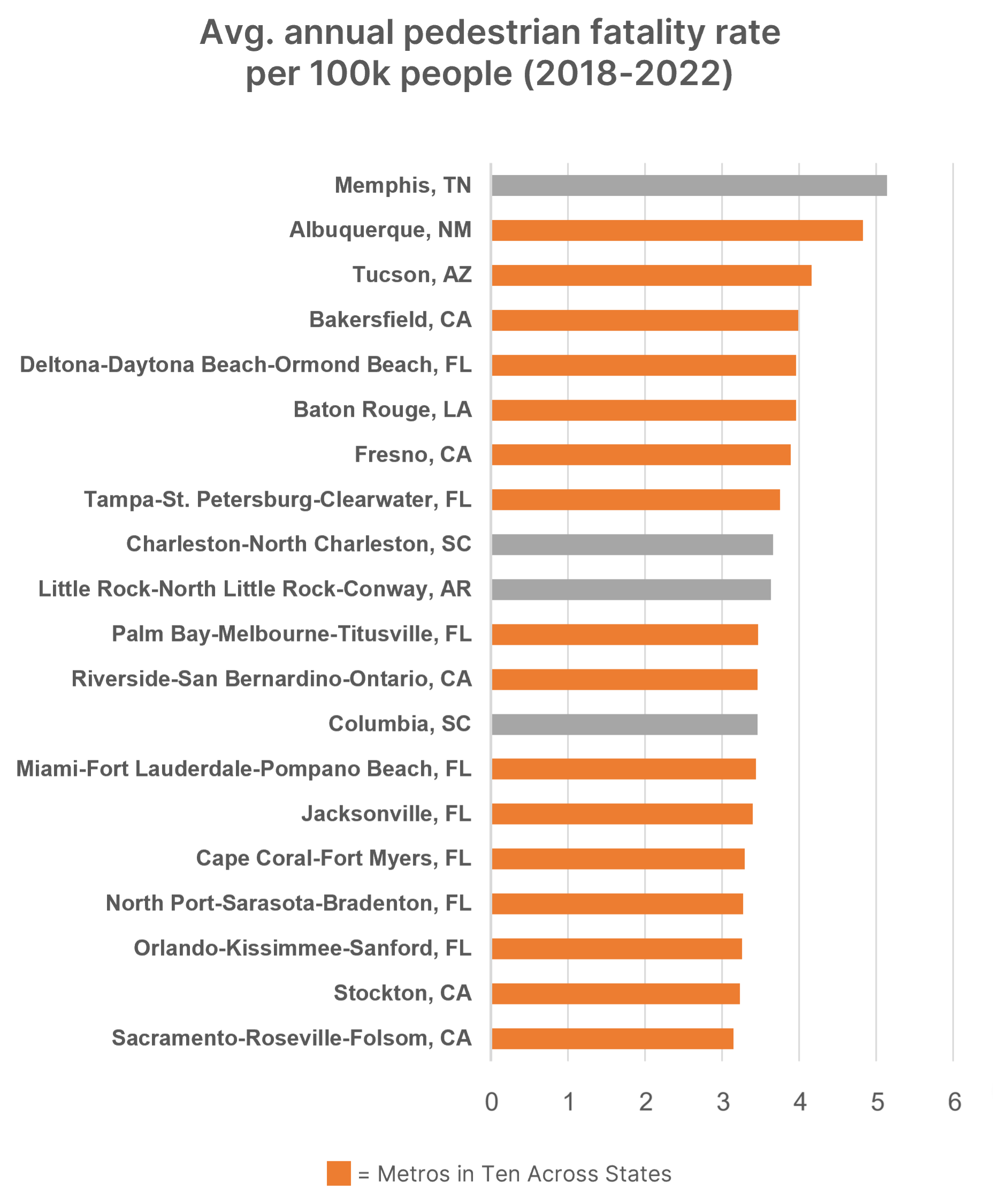

While transportation safety is an issue throughout the U.S., some metros prove more dangerous for pedestrians than others. Of the top 20 most dangerous metro areas identified in Smart Growth America’s study, only four were found outside of the Ten Across corridor.

These 20 metros were similarly ranked over a previous 2013-2017 study period and all but two saw increases in fatalities during the 2018-2022 study. Based on their figures, rates of pedestrian death now far outpace population growth rates in the Sunbelt, making safer road design a necessity for this region of the country.

According to the DC-based nonprofit, many pedestrian incidents are considered the result of poor urban planning and road design which tend to prioritize the movement of vehicles over humans.

American dependence on automobiles requires that we share significant space with them. Among other countries, only New Zealand rivals the U.S. in rates of personal vehicle ownership, and our roadway system is twice the size of China’s. A steady incline in U.S. pedestrian deaths even as rates in other nations are falling suggests there is a cost to this relationship with our vehicles.

Aside from declining pedestrian safety, how else has our deference to personal vehicle travel impacted infrastructure, community, and culture? Let’s look at some Ten Across trendlines to better understand the roots and impacts extending from this critical topic, as well as opportunities for solutions.

The U.S. and the Automobile

This epidemic continues to grow worse because our nation’s streets are dangerous by design, designed primarily to move cars quickly at the expense of keeping everyone safe.

Smart Growth America, “Dangerous by Design”

The name and concept for the Ten Across project comes from the U.S. Interstate 10, a product of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. As the first and last major nationwide infrastructure project to provide residents of the contiguous U.S. an efficient and affordable connection to one another, this program solidified our reliance on cars and their cultural associations with freedom.

Cars remain our foremost means of travel, and are such a priority that while the entirety of the nation’s urban areas consume just 2% of our land mass, 20% is directly impacted by the miles of rural roads and highways designed for use by personal and commercial vehicles. The American Society of Civil Engineers found that the U.S. transit system occupies just over 240,000 miles— a figure that is quickly dwarfed by our four million-mile roadway network.

As a result, Americans are accustomed to driving long distances at accelerated speeds to get to their homes, recreation and work, and state governments find themselves in a constant cycle to provide more vehicle lanes and speed allowances along these routes. This video from Grist shows how speed limit increases on surface streets in Los Angeles and other cities are rarely determined directly by the community or policy leaders, but rather adapted to the average speed that at least 85% of drivers choose to go—including those that are speeding.

Meeting the demands of greater and faster road travel also comes at a large cost to taxpayers. The Urban Institute estimates state and local governments dedicate an average 6% of direct general funding to highways and roads every year ($206 billion in 2021), compared to just under 2% for housing and community development. This tolerance for speed and the prioritization of land and budget for vehicles likely contribute to communities in the Ten Across geography becoming more dangerous for those both inside and outside the vehicle.

Inequities in U.S. Transportation Policy and Infrastructure

…Black Americans… are killed at double the rate of white Americans. It’s more likely in part because Black neighborhoods have more high-speed roads with a lack of facilities for people walking.

Smart Growth America, “Dangerous by Design”

The Interstate Highway system has left a greater mark on our landscape and culture than just our desire for speedy travel. America’s pervasive road infrastructure is also responsible for the destruction and endangerment of countless minority communities.

Smart Growth’s “Dangerous by Design” study found that Black pedestrians are dying at twice the rate of white pedestrians. As the study’s title would suggest, this discrepancy is a result of infrastructure design, which often reflects the nation’s history of discriminatory zoning, housing, and transportation policies in terms of where these pedestrian incidents are most likely to occur.

When highway construction began in the 1950s, the nation faced a housing crisis as soldiers were returning home from World War II. Though the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation was introduced to help, it systematically denied members of minority groups access to available housing aid and sent surveyors to rank U.S. neighborhoods based on their demography—those with large minority populations were marked red. This negative grading devalued properties and disempowered residents, making these communities prime targets in site selections for disruptive and polluting federal, state and local infrastructural and industrial projects for decades afterward. The Ten Across Conversations podcast has covered this history with Dr. Robert Bullard, author of Highway Robbery: Transportation Racism and New Routes to Equity.

Today, redlined communities are three times more likely to be bisected by an interstate highway. Further, as the Smart Growth America study highlights, the autocentric nature and influence of these infrastructure projects often left majority-Black communities with fewer supportive pedestrian facilities.

Benefits of Moving Away from Autocentric Design

Smart Growth America argues that pedestrian death and injury could be reduced through different design choices. Through the example of Memphis, ranked as the most dangerous city for pedestrians, the report offers specific recommendations for pedestrian infrastructure improvements that can benefit Ten Across cities.

Jon Jon Wesolowski, known as “The Happy Urbanist” on TikTok, recently recorded a walk to a local park to illustrate failures to provide safe walkable spaces in his hometown, Chattanooga, Tennessee. His tour identifies needs such as improved shade to reduce heat exposure, “daylighting” regulations to prevent vehicles from parking on or too close to crosswalks, reduction of vehicle lanes and increase sidewalk size, among many other items.

Wesolowski’s video also demonstrates the impact of poor pedestrian design on local businesses. Urban and semi-urban streets in Sunbelt communities often have infrastructure which belong on highways, such as metal guardrails, within their communities. These harsh barriers lining sidewalks outside business storefronts not only create a visual understanding that the space is designed to prioritize fast-moving cars, but they also disrupt easy access to stores, discouraging foot traffic and inhibiting sales in the long term.

Beyond limiting physical risks, communities that prioritize walkability are known to benefit from several positive health impacts that improve the resilience of their residents. Researchers at Texas A&M University found that walkable communities—meaning those with more intentional pedestrian and bicyclist infrastructure—generate greater physical activity and sociability among their residents than autocentric communities do.

A Conversation on Texas’ Freeway Fighters and their Push for Safer Communities

Many of the people who showed at Stop TxDOT I-45’s meeting…were outraged…They had long lived with the impacts of Houston’s auto dependency. They had asthma. They’d lost loved ones to car crashes. They’d had close calls biking around the city.

Megan Kimble in City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways

Today, many national and local groups are forming to challenge the presence and negative impacts of U.S. autocentric infrastructure. By seeking to remove and replace aging and particularly disruptive sections of urban expressways in the U.S. with more supportive pedestrian and urban infrastructure, this network of advocates is carrying on the legacy of many who fought the initial construction of the Interstate Highways in the 50s.

Many freeway fighter groups are based in Texas, a state where the impacts of transportation discrimination are especially visible. Megan Kimble, independent journalist, author, and a native of Austin, Texas, profiles a cast of residents dealing with the seemingly unstoppable force of roadway expansion and the Texas Department of Transportation in her new book, City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways. With this exploration, she urges us to consider how our roads are governed and whether communities are equitably represented in the processes that determine traffic congestion and pedestrian safety.

I am captivated by the idea of highway removal — the idea of replacing the violent, dangerous structures that contour our cities with parks and promenades and places to live — because it makes so much else possible.

Megan Kimble in City Limits: Infrastructure, Inequality, and the Future of America’s Highways

Megan also delves into the environmental and human toll of business-as-usual roadbuilding. Around 40,000 people die in vehicular accidents every year, and 10% of U.S. traffic fatalities occur in Texas. Furthermore, Texas’s on-road emissions in 2018 accounted for .5% of worldwide emissions. As her book points out, none of these impacts takes political precedence over making car travel faster and easier in the state.

Listen to Ten Across founder Duke Reiter’s and City Limits author Megan Kimble explore a history of U.S. transportation policy and infrastructure and how it is influencing life along Interstate 10 today on the Ten Across Conversations podcast.

Is there a story we might have missed?

Have ideas for topics we should watch or who we should interview next?

Let us know: tenacross@asu.edu.